The Beatles

The

Beatles are unquestionably the best and most important band

in rock history, as well as the most compelling story. Almost

miraculously, they embodied the apex of the form artistically,

commercially, culturally and spiritually at just the right time,

the tumultuous '60s, when music had the power to literally change

the world (or at least to give the impression that it could,

which may be the same thing). The Beatles are the archetype:

there is no term in the language analogous to “Beatlemania.” The

Beatles are unquestionably the best and most important band

in rock history, as well as the most compelling story. Almost

miraculously, they embodied the apex of the form artistically,

commercially, culturally and spiritually at just the right time,

the tumultuous '60s, when music had the power to literally change

the world (or at least to give the impression that it could,

which may be the same thing). The Beatles are the archetype:

there is no term in the language analogous to “Beatlemania.”

Three lads from Liverpool — John Lennon, Paul McCartney

and George Harrison — came together at a time of great

cultural fluidity in 1960 (with bit players Stu Sutcliffe and

Pete Best), absorbed and recapitulated American rock ‘n’

roll and British pop history unto that point, hardened into

a razor sharp unit playing five amphetamine-fueled sets a night

in the tough port town of Hamburg, Germany, returned to Liverpool,

found their ideal manager in Brian Epstein and ideal producer

in George Martin, added the final piece of the puzzle when Ringo

Starr replaced Best on drums, and released their first single

in the U.K., “Love Me Do/P.S. I Love You,” all by

October of 1962.

Their second single, “Please Please Me,” followed

by British chart-toppers “From Me to You,” “She

Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “Can’t

Buy Me Love” (all Lennon/McCartney originals), and the

group’s pleasing image, wit and charm, solidified the

Fab Four’s delirious grip on their homeland in 1963.

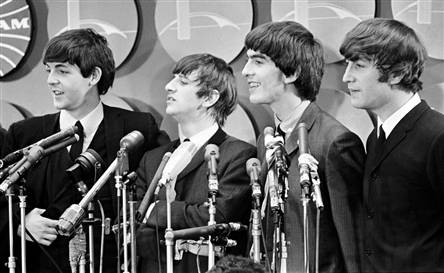

But it was when the group arrived in the U.S. in February 1964

that the full extent of Beatlemania became manifest. Their pandemonium-inducing

five-song performance on the Ed Sullivan Show on February 9

is one of the cornerstone mass media events of the 20th century.

I was five at the time — my parents tell me I watched

it with them, but I honestly don’t remember. I do remember,

though, that the girls next door, four and six years older than

I, flipped over that appearance and dragged me into their giddy

madness soon thereafter. I loved “I Want to Hold Your

Hand,” the Beatles’ first No. 1 in the U.S. (they

had 19 more, still the record), more than any other song I have

ever heard, or almost assuredly will ever hear, with a consuming

intensity that I can only now touch as a memory.

The Beatles generated an intensity of joy that slapped tens

of millions of people in the face with the awareness that happiness

and exuberance were not only possible, but in their presence,

inevitable. They generated an energy that was amplified a million

times over and returned to them in a deafening tidal wave of

grateful hysteria.

A partial result of that deafening hysteria was that the band

became frustrated with their concerts and stopped performing

live after a San Francisco show on August 29, 1966. Yet even

this frustration bore fruit, as the four musicians, aided almost

incalculably by producer Martin, turned their creative energies

to the recording studio, producing ever more sophisticated and

accomplished albums “Rubber Soul” (1965, “Drive

My Car,” “Norwegian Wood,” “You Won’t

See Me,” “Nowhere Man,” “Michelle”),

“Revolver” (1966, Harrison’s “Taxman,”

“Eleanor Rigby,” “Here, There and Everywhere,”

“Yellow Submarine,” “Good Day Sunshine,”

“And Your Bird Can Sing”), the majestic and epochal

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967,

title track, “With a Little Help From My Friends,”

“Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds,” “When I’m

Sixty-Four,” “A Day In the Life”).

Though centrifugal force began to take its toll, they still

managed to produce three more album masterpieces, double-album

“The Beatles” (1968, a.k.a. “The White Album,”

with “Back In the USSR,” “Dear Prudence,”

“Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da,” Harrison’s “While

My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “Blackbird,” “Birthday,”

“Helter Skelter”), “Let It Be” (recorded

in early 1969 but not released until 1970, with the title track,

“Two Of Us,” “Across the Universe,”

“I’ve Got a Feeling,” “The Long and

Winding Road” and “Get Back”), and the fitting

climax “Abbey Road” (1969, Harrison’s “Here

Comes the Sun” and “Something,” Ringo’s

“Octopus’s Garden,” “Come Together,”

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” “I Want You,”

“She Came In Through the Bathroom Window”).

They made an incredible promise and instead of backing down

from that promise they delivered and delivered and delivered

for eight years until the full implications of the promise finally

hit them: they were staring into the jaws of an insatiable,

ravenous beast that was no less beastly because it smiled and

waved and gave them money. The Beatles finally suffered a collective

inability to pretend that the beast was not a beast, and in

1970 they broke up and returned to being human.

Beatlemania redux

A small but significant slice of the Beatles’ magic came

back in 1986 with release of the classic John Hughes teen flick

“Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” wherein Matthew

Broderick’s title character lip-syncs the early Beatles

classic “Twist and Shout” (ironically, a song they

didn’t write) from the top of a float in a downtown Chicago

parade.

John Lennon sang “Twist and Shout” as though the

words were joyful corrosive poison, that his only hope of survival

was to expel them with all the vehemence that his rhythm-besotted

body could muster, and so does Ferris in the scene. Paul and

George’s responses matched John’s zeal at the end

of each stanza with their delirious “Ooohs.” They

were enjoying themselves so much that this song seemed the most

important thing in their lives at that moment. The Beatles knew

the awesome responsibilities of pleasure.

Ferris lips lustily, the frauleins on the float shimmy and shake

and bounce off of Ferris like electrons, the thousands in the

crowd sing along from the pits of their pelvises. Chicago jams

as one, recreating the Beatles’ amazing real-life feat

of a unifying mass-madness that changed people’s lives

for a time.

When I saw the movie in the theater in ‘86, people actually

stood up and danced in the aisles. How could they not? The “Twist

and Shout” segment was the most exciting and joyous musical

moment in a movie since the Beatles own “A Hard Day’s

Night” (1964), and was the perfect climax to Ferris Bueller’s

film exploits.

The public was so wistful for Beatlemania that “Twist

and Shout” returned to the charts for 15 weeks that year,

a brief but sweet reminder of the real thing.

|